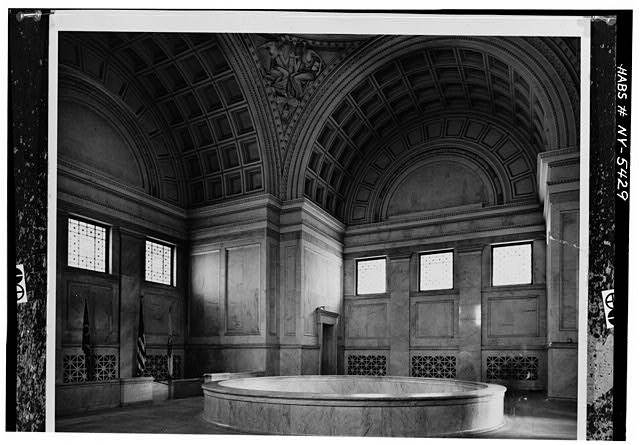

"It was intended to be a very dignified mausoleum. Any intrusion of that kind is a compromise with the purpose of the tomb."

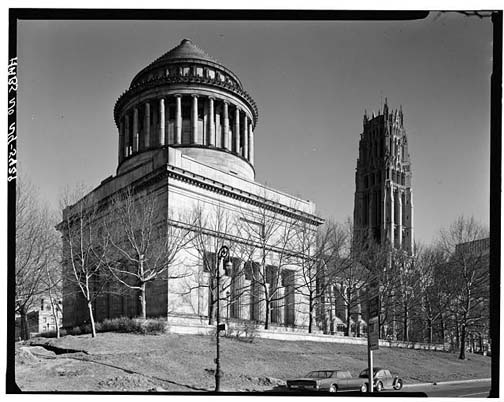

The structure rises 150 feet above the ground and symbolically faces south. It has an eclectic architectural style inspired by different and distant emblematic buildings such as The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, Napoleon's Tomb in Dome des Invalides, Tropaeum Alpium in La Turbie, and Emperor Hadrian's Tomb in Rome. These influences aimed “to produce a monumental structure that should be unmistakably a tomb of military character (TGMA 2012)”

Grant's Tomb was New York's biggest touristic attraction in the early 1900s. In 1958 the National Park Service was conferred authority to manage the Tomb. However, in the 1970s, the monumentality of the Memorial was reconfigured and it became a meeting point for drug dealers, crack consumers and homeless. Moreover, it and was affected by vandalism and graffiti (Allon 1997).

In 1991, Columbia student Frank Scaturro volunteered with the National Park Service and became an activist for the restoration of the tomb. In 1994, Scaturro’s campaign got the attention of two Illinois state lawmakers who sponsored a resolution to transport the tomb to Illinois in case the NPS did not restore Grant´s tomb. Later on, in the same year, the United States House of Representatives approved legislation to “restore, complete, and preserve in perpetuity the Grant's Tomb National Memorial and surrounding areas”.

However, a previous effort to stop graffiti and vandalism at Grant's Tomb was made in 1972, when this pretentious mausoleum was exteriorly intervened by the NPS through a public arts project that hoped to by to involve diverse members of the Morningside Heights neighborhood. Between 1972 and 1974, Pedro Silva, a Chilean artist, conducted a team of 2500 local adults and children volunteers that constructed a colorful 350 feet mosaic tile benches that snake around Grant's tomb. The mosaic designs contain obvious Gaudí’s reminiscences, and have been compared to “an unfolding comic book”. They include a portrait of General Grant, depictions of his travels and accomplishments, and other images such as animals, flowers and a New York taxicab.

In 1995 the NPS started a $1.6 million renovation in the monument. The initial project considered removing the mosaics. This action reactivated an old controversy about this artistic intervention in Grant’s tomb. On one side, some Civil War enthusiasts and the NPS considered that the mosaics clashed with the site and trivialize its historical significance and architectural and aesthetic character. Moreover, for the Grant Monument Association the construction of the mosaics took place in the context of a “general decline of patriotism and misdirection on the part of the NPS” and, therefore, they favored their removal.

On the other side, local officials, preservationist and City Arts, a nonprofit group that sponsored the project and other public art projects, considered the mosaics a prominent work of public outdoor art in NY that had become part of the traditional monuments in NYC and, therefore, should be preserved. In this sense, they referred that the monument have had a number of modifications along its history and that the mosaics where only the last moment in this process. Finally, their protests were taken into account and the mosaics removal was stopped and even more, they were recently restored by children and adults from the surrounding neighborhood, again, under the conduction of Silva.

The arguments deployed in this controversy bring central subjects that are still part of the debate about the relations between tradition, change and discipline, and the symbolic and material configuration of landscapes. Grant’s tomb was apparently intended to be a “very dignified mausoleum” (Mindlin 2004) evoking classical styles, but became later a mayor touristic attraction, afterwards a lumpen-park and finally was incorporated into the symbolic universe of the locals through a ludic modification.

This case let us have a very close view on how monuments play a central role in the construction of social memory, and how the struggle for controlling this process can radically transform a particular landscape.

References

Allon, Janet. (1997). “Mosaic Benches Face Unseating At Grant's Tomb”. The New York Times. Published: March 30.

Kahn, David. (1980). General Grant National Memorial Historical Resource Study. NPS

Mindlin, Alex (2004). “Neighborhood Report: Morningside Heights; Dust-Up Over Center For Grant's Tomb”. The New York Times. Published: August 01, 2004

The Grant’s Tomb Monument Association Website. http://www.grantstomb.org/

7 comments:

wow that second photo...the tomb really does have the look and feel of a mausoleum...just shows how much the landscape has changed. what i find interesting is that americans tend to have a special interest in historic buildings abroad, especially in europe. yet at home, there is more neglect. this interest, it could be argued, is more grounded on the whole tourist experience, but i do think there is a difference between say americans and europeans when it comes to an issue like this.

I was reminded of Grant's Tomb earlier in the semester, when we were thinking about places and spaces of death. Your discussion of this conflict is really interesting - as it highlights what might be a kind of conflict between the tendency to see the site as nationally/politically significant, as opposed to it being locally significant. Furthermore, it is interesting to consider how aesthetics figures into this kind of conflict.

Sorry, above comment is from Jay Ramesh - I think I have an old blogger account under the name "Raj" so my name didn't show up.

This is fascinating, and I like your discussion of memory and conflict over shared spaces/monuments for remembering. I'm not sure I agree, Nasser, that there is a simple European/American divide here though (although I may not understand what you mean - I take you to mean that Europeans are more conscious of preserving their historical monuments in a state of "purity" at home, whereas Americans tend to only feel this "pristine" preservation to be relevant abroad). I think immediately of the Berlin wall graffiti, for instance, which is constantly changing and reinventing that space in the context of memorializing a conflicted past. Even for something less contested, I think of Trafalgar Square, where there are continuously changing art and performance installations on the plinth. Although perhaps this is different because it is never permanent? In any case, I think the way memory is treated locally as opposed to nationally is a really interesting point, as Jay notes, and this post brings it out beautifully.

alison, i don't think neither of us are making especially simplistic points, but perhaps coming from different analytical frameworks. although i am probably more to blame for your interpretation, given the words and styles i used to convey my point on a blog post. what i'm trying to get at is that in america, there is perhaps a weaker attachment to locality, than say exists in britain. mobility is also something that has more currency in the us. americans are more likely to pack and move to another place in the country. there's the whole road trip phenomenon (think of the wave of movies in the us, none i can think of in england). this surely needs to be considered in any analysis of locality and buildings such as the mausoleum. it might out analysis a little more difficult to carry out, since a focus on purely "local" matters appears more contained and thus easier to deal with.

Personally, I find the current mish-mash of austere tomb and abstract, organic, mosaic retaining wall a very strange combination, and I'm glad, Gustavo that you've decided to bring it up. On the one hand, the tomb is symbolic of America's past, and at the same time, like Jay said, it represents a local community. I think, also, that it is significant to note Grant's personal history as the general that ended of the Civil War. It is significant, I think that his tomb is located in an area of New York City that for a long time was dominated by a largely African American population, and the addition of the retaining wall, I think looses some of its silliness when viewed in light of the kind of neighborhoods that surrounded the mausoleum in both past and present.

And a question that I just thought of. How should we in the present view the mausoleum combined with the oddly disjointed rainbow mosaic wall? Should we think of them and view them together as a representation of the whole site in the present? Or view them as two separate acts of commemoration? Do they even fit together so that they can be seen as a whole?

Post a Comment