This weekend, I found myself at a place where I never ever imagined I would be. I made a decision to accompany my cousin on a three-day Catholic retreat at the Franciscan Friars of the Atonement's Graymoor Spiritual Life Center in Garrison, New York. Aside from my early years at Catholic elementary school, I never particularly considered myself religious especially after a number of disagreements with certain interpretations of Catholic doctrine. Disagreements which some priests would say "make me not Catholic." Nevertheless, I wished to support my cousin on his spiritual journey since his deployment to Afghanistan is drawing near, and I just couldn't deny him of the one request he has ever made of me. Plus, I figured the experience had great semiotic potential. [End of disclaimer]

On our drive to Garrison, I couldn't help but be in awe of the Hudson Highlands. The route to the Graymoor took us further and further up a mountain, and my cousin remarked, "I guess the Franciscans wanted to be 'closer' to God." It doesn't surprise me that monasteries are usually found in isolated, remote areas with larger than life backdrops of nature. And like the ancient Egyptians and Mayans, it makes sense that spiritual structures were built in such a way so as to "reach the heavens." As I drove up the spiraling road, I couldn't deny the transformation of my mood and attitude to a kind of humble reverence as invoked by the physical being, place and elevation of the mountain. But a better example of this physical place-induced transformation was on Saturday, during the night of atonement.

The sacrament of Reconciliation, according the Catholic tradition, is celebrated when you confess your sins to a priest who then absolves you of your sin in a contract-like manner, where it is only considered complete if you follow through with reflection and prayer according to the instruction of the priest. Since there were 46 of us at the retreat, we were asked to write a list of things we wished to discuss with the priests for the sake of efficiency as waited for our turn at confession. Needless to say, this gave me a lot of time to reflect, and even more time to observe through semiotic lenses.

Confessio

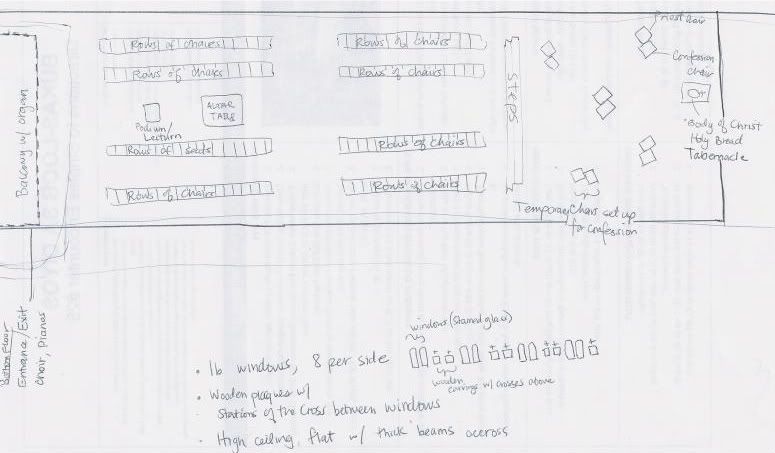

n took place in a modern chapel that was modest in size and interior decoration - simple white rectangular walls and ceiling, carpeted floors, simple arch windows, and movable chairs and tables. (See hand drawing of floor plan since I couldn't take any pictures). Note: The Franciscans take after St. Francis of Assisi, who was the son of a rich merchant and a soldier. He gave up all of his possessions, lead a life of simplicity and bare necessity, giving up his possession to serve the Christian God among the beggars.

n took place in a modern chapel that was modest in size and interior decoration - simple white rectangular walls and ceiling, carpeted floors, simple arch windows, and movable chairs and tables. (See hand drawing of floor plan since I couldn't take any pictures). Note: The Franciscans take after St. Francis of Assisi, who was the son of a rich merchant and a soldier. He gave up all of his possessions, lead a life of simplicity and bare necessity, giving up his possession to serve the Christian God among the beggars.

Anyone that has ever been to confession, or watched a confession scene on film, will notice that the setting is always in "darkness." Confession usually takes place in the privacy of small, narrow confession boxes, and you usually have the option to face the priest directly, or through a wall with an unrevealing wire mesh "window."

That night, however, (perhaps it has something to do with the Franciscan order?) confession took place out in the open. Chairs for confession were set up at the front of the chapel on a slightly elevated area that was well lit and in the same area as the holy tabernacle (a sacred vessel where the Eucharist, or Body of Christ is stored). The chairs were set up to have you sit side by side with the priest, yet facing him at the same time (see demonstrative photo).

The arrangement of the chairs were in such a way where your back is turned to the congregation, and you could not see nor hear the other confessors. The positioning of the chairs allowed for an optional direct gaze, but also put you within arms reach as he places his hand atop your head for absolution.

The arrangement of the chairs were in such a way where your back is turned to the congregation, and you could not see nor hear the other confessors. The positioning of the chairs allowed for an optional direct gaze, but also put you within arms reach as he places his hand atop your head for absolution.After confession, each individual was allowed a turn at burning our "list of sins" in a pit outside of the chapel by the entrance.

It took about two hours for 46 people to complete this ritual, and as I was sitting and observing in the chapel, Peirce and Bakhtin came to mind. Purely symbolic in nature, the physical act of burning did not seem to affect me or "lift off burdens" as much as reflecting on my transgressions within the chapel walls, or speaking with the priest in an area feet away from the omnipotent presence exuding from the chronotopic tabernacle - the loci of the transubstantiated body of the 2000+ Son of God to some, or a prophet to others. As a young girl, this mysterious tabernacle always seemed intimidating and untouchable, and traces of this brute feeling (secondness) prevailed that night by some habit of mind.

Believer or non-believer, the chapel induced a sensorial experience with a tendency to humble. At the far end of the church, murmurs can be heard, at the center - whispers, giggles and tears, and at the entrance, a solemn piano.

No comments:

Post a Comment