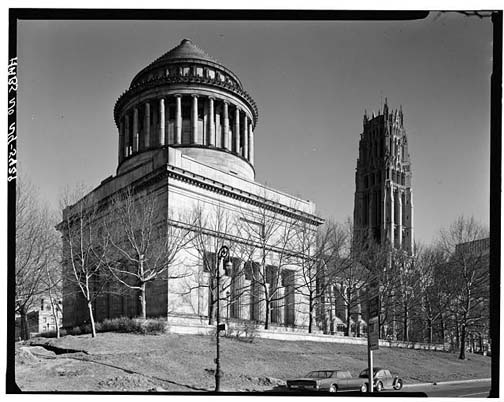

When I first told my father I was considering applying to Columbia University, he told me that the campus was like an oasis. He said that you walk from the busy city in through the gates of the campus, and it was quiet and green and beautiful. Since then, I've heard many other people describe Columbia's campus this way, including in this class and in these blog posts. Other posts have mentioned its situation atop a hill, its classical architecture, its exclusionary exterior, its elegant brick work, and so on. And so I was quite surprised to find, in my research on Columbia's associated neighbor, Barnard College, that in fact, across the street from Columbia had once been comparably far lusher than Columbia.

Barnard College was founded in 1889 and began a rented brownstone downtown by Columbia's original location. In 1896, a few years after Columbia moved up to Morningside Heights, Barnard followed it uptown and moved to a small, one acre plot directly across Broadway (Barnard Archives: "Chronology"). Maps of Barnard College are included in the maps of the Columbia University campus, published annually in the Columbia University Catalogue. Below is a map from 1898, which depicted Barnard's initial campus, consisting of three inter-connected buildings on the block between 119th and 120th streets.

|

| Courtesy of the Columbia University Archives |

|

| Courtesy of the Columbia University Archives |

The three buildings were known as Fisk, Milbank, and Brinkerhoff Halls, although now all three are referred to as Milbank Hall. Below is a sketch of the buildings and their exterior courtyard from circa 1898. As you can see in the sketch, the building emulates the classical influences Columbia is known for, as well as the red brick and ivy-covered facade.

|

| Taken from the publication, "Barnard College, New York City, Plans of the new building on the Boulevard at One-hundred and nineteenth Street", published by Barnard College. Courtesy of the Barnard College Archives. |

|

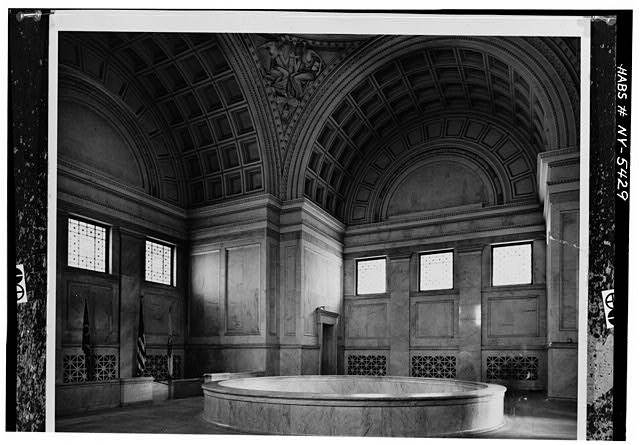

Even then, Barnard and Columbia were closely affiliated as they are now. The publication cited in the caption above states that fourth year Barnard women could take classes at Columbia. In addition, Barnard students had full use of the Columbia library, and so Milbank contained only a reading room and reference desk.

Several years later, in 1907, Brooks Hall was completed, and was a student dormitory. It capped the bottom of the present Barnard campus. Although 119th street cut between the Milbank complex and the rest of the Barnard campus until the 1960s, the current campus still runs between Brooks and Milbank, and has not expanded. Dormitories have been built or acquired outside the campus in the Morningside Heights neighborhood in order to house the present student population, but the campus itself has remained the same size. Below is a map of Barnard's campus in 1910. In the maps, you can see the plan of paths and tennis courts, as well as the buildings. In addition, the squares and lines around the outside of the bulk of campus represent an iron fence. Like Columbia, as has been discussed in previous blog posts, Barnard restricted entry to its campus from early on. Also below is a photograph of campus at that time.

|

| Courtesy of Columbia University Archives |

|

| Courtesy of the Barnard College Archives |

The wooded area by the tennis courts was known as "The Jungle," and in my opinion epitomizes the 'oasis' ideal, often associated with Columbia. This verdant landscape contained numerous types of trees, winding paths, benches, etc. Below is an aerial view of "The Jungle," taken during the 1950s. Also below is a circa 1950 image of two Barnard students in the "Jungle" area of campus, which appears quite idyllic.

|

| Courtesy of the Barnard College Archives |

|

Aerial

view of

the Jungle, looking north, circa 1950s.

Courtesy of the Barnard College Archives | | | | | | | | | |

|

By this time, a third building existed on campus, then known as Students' Hall, and now called Barnard Hall. The layout of the campus is on the left part of the image below, the layout of Barnard's campus is visible next to its larger neighbor. As you can see, by this point in time much of Columbia's campus had been developed, although 116th street was still open to traffic, and the southern part of campus was still open at the bottom.

|

| Map from 1918, Courtesy of the Columbia University Archives |

Student's Hall was followed shortly by an entrance gate, first labeled on the maps in the 1924-1925 Columbia Directory. The picture below shows the "Helen Hartley Jenkins Geer Memorial Gate," or the "Geer Gate," which still stands at Barnard's main entrance today. Behind it is the ivy covered Students' Hall. Even though this is the most built-up part of Barnard's campus at this time, it still gives the impression of gates enclosing a garden.

|

| Geer

Gate ca. 1944. Photograph by

Paul Parker,

courtesy of the Barnard College Archives. |

Although during the 1950s, several more buildings were added to the southern part of campus, adjoining Brooks, the Jungle and tennis courts remained intact until the 1960s, when the Lehman Library was built. Little by little, Barnard began to follow in Columbia's footsteps of filling its borders with buildings and shutting out the rest of the city. In the below picture, depicting the view of Brooks, Reid, and Hewitt along 116th street (just outside the southern edge of campus), Barnard has adopted Columbia's pattern of giving outside viewers a cold image of the backs of buildings.

|

| Courtesy of the Barnard College Archives |

Today, while Barnard's campus still has some green space, nearly all of its borders are filled by buildings. I might still consider it to be somewhat of a miniature oasis, but after looking at the stunning pictures of the "Jungle," I realize that it is not even close to its former natural beauty. Like Columbia, Barnard was pressured by space constraints and an increasing student body, requiring additional facilities. Barnard's predominantly classical architecture, imposing iron gates, and ivy covered brick match the style of Columbia's campus, linking the two together aesthetically. In its early stages, Barnard only blocked off the city around it to the north, south, and west, leaving open its side facing Columbia, but in the last 30 years it has blocked off its western side as well. Perhaps this is significant, relating to Barnard and Columbia's relationship over time. The recent onslaught of negative online comments highlights the present tension between the schools, particularly since Columbia became co-ed, forcing new definitions and purposes for each. Interestingly, Columbia became co-ed only 5 years before Barnard constructed Centennial Hall (now Sulzberger Hall), the first building to majorly obstruct the site lines from Columbia into Barnard, further closing the eastern side of campus. Perhaps Barnard's closing off of itself from Columbia is defensive- it is claiming its right to remain an independently run but affiliated institution for women, even though it is no longer the sole educator of women in the University.

Sources:

Barnard College Archives

Columbia University Archives- Buildings and Grounds Collection

Barnard College Archives.

Chronology. <http://barnard.edu/archives/history/chronology>

Barnard College Archives.

History of the College. <http://barnard.edu/archives/history>

Barnard College. 1989 (?)

Barnard College, New York City, Plans of the new building on the Boulevard at One-hundred and nineteenth Street. Pamphlet, published by Barnard College.